Over the course of our careers, many of us experience people in leadership roles (including those who lead projects and/or people) who misuse their power or authority. In these situations, we may feel demoralized, intimidated and ultimately excluded from being able to make a difference.

If we’ve had authority, maybe we’ve been that someone. The drive for importance, control, and power is seductive!

At the 2016 International Leadership Association (ILA) Conference, Ronald Heifetz, founding director of Harvard University’s Center for Public Leadership, delivered a keynote entitled “Authority, Trust and the Challenges of Inclusion.” He invited attendees to reflect on their feelings about authority as part of an exploration of the meaning of authority.

What are your views or feelings about authority? Think of a lived experience that represents those views or feelings.

Authority is typically a ’conferred power’. It involves a social contract in which those in authority are entrusted with responsibility in exchange for providing specific service(s).

We expect those in authority to carry out their responsibility with integrity and competence (i.e., have the requisite expertise and know-how), and to provide direction, order, resources, and protection. Protection, Heifetz notably added, includes guarding those they serve from uncertainty. In these complex times, however, those in authority don’t always know what to do. What then?

Heifetz illustrated that people in authority often try to maintain trust (their “authorization”) by claiming that they know how to navigate complexity even when they don’t. A better approach, he offered, is to tap the broader collective intelligence. Doing this, however, requires deep listening.

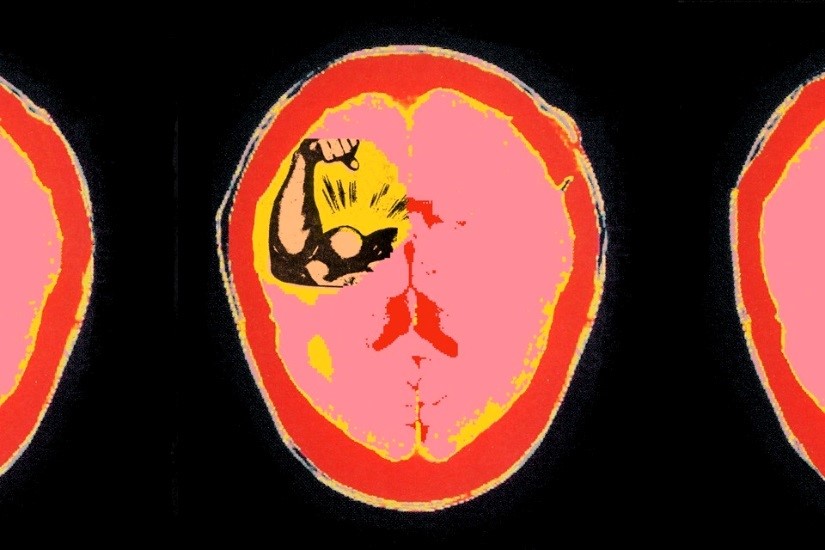

In July 2017, the Atlantic published a provocative article entitled Power Causes Brain Damage, which highlights the concept of mirroring, a form of very deep listening (resonance). “Once we have power, we lose some of the capacities we needed to gain it in the first place,” suggests research conducted at McMaster University. Twenty years of UC-Berkeley research netted similar observations: “Subjects under the influence of power…acted as if they had suffered a traumatic brain injury—becoming more impulsive, less risk-aware, and, crucially, less adept at seeing things from other people’s point of view.”

This is bad news! Worse, exerting effort fails to increase mirroring ability, according to the research. Instead, the research suggests that we recall situations when we’ve felt powerless. It’s this act of intentional recall that can connect us with the empathy that is required to mirror others effectively.

So, as Heifetz invited his ILA audience to do, consider: what are your views and feelings about authority? Think of a lived experience that speaks to those views or feelings.

Then, recall a situation in which you felt powerless, and reflect on how you might include others more fully in your current role in HR@UW.